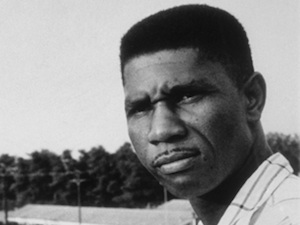

June 12, 2013, marked the 50th anniversary of the murder of Medgar Evers. Evers, a heroic leader of the Mississippi wing of the Southern Freedom Movement, was shot down after a long night working at the Jackson NAACP office by Byron De La Beckwith, an active member of the white supremacist movement. Evers' killing, a cowardly act, served only to further unmask the reactionary pro-Jim Crow forces for exactly what they were and, contrary to their hopes and wishes, only further emboldened Blacks and their allies to continue the struggle. Today, as it has since that fateful day in 1963, Medgar Evers stands as a shining example of dedication to the cause of human freedom.

Early days

Medgar Evers was a native of Mississippi, born in 1925 in the small town of Decatur. Born to a large farming family, like many Blacks in rural southern areas Evers had to travel miles by foot to graduate high school. From 1943 to 1945, Evers served with the United States Army in Europe during World War II, finishing his service as a sergeant. Following his service, Evers attended what is now Alcorn State University, a historically Black university, graduating in 1952.

While briefly serving as an insurance salesman in the employ of Mississippi businessman and activist for Black equality T.R.M. Howard, Evers' true calling was to be dedicated full-time to fighting the reactionary Jim Crow system of segregation.

Evers had been a member of the NAACP while in college, and as his wife Myrlie described it, “deeply involved in racial affairs.” While working as an insurance salesman in the Black community of Mound Bayou, he became active in the Regional Council of Negro Leadership headed by Howard. Evers attended their massive annual meetings in the early 1950s that routinely drew thousands of people, including many of the names that would later become prominent in the civil rights activities of the 1960s.

'He loved the work'

Evers, on his own initiative, organized NAACP chapters in different parts of the state, which made him the natural choice when in 1954 the organization was looking to appoint a state field secretary. Myrlie Evers relates: “We knew the job was dangerous. From the beginning we accepted the possibility that any of us might be killed … but he loved the work.”

Evers became something of a one-man army, jumping into seemingly every case where the rights of Black people had been impinged, including many killings. When Emmett Till was brutally murdered in 1955, it was Evers, dressed as a common sharecropper, who traveled the area gathering evidence and finding witnesses.

Evers was not seeking martyrdom in the service of a righteous cause, however. As was widespread among southern Blacks, Evers was an advocate of self-defense. He developed plans to protect himself and his family, and actively made plans to counter potential escalations of white violence. Myrlie Evers related to one author a conversation about the need for Blacks to be armed and prepared: “You must always be prepared for whatever comes our way.”

Equally as important to understanding Evers is a statement from that same interview where she explained that his strategy of self-defense was based on his belief that it may not be possible for whites and Blacks to live in harmony and that his thoughts dwelled on “building a nation … of Black people.”

Freedom Now!

Evers was motivated by his desire for freedom above all else. His tactics tested the willingness of the racist U.S. to grant concessions, while preparing for a national independence struggle if necessary. This is one of many factors in revealing the shallowness of understanding the Civil Rights era as an “integrationist” struggle. There was a range of ideologies and commitments among Blacks during the 1950s and 1960s, but the central theme was freedom, or more exactly national liberation—relief from the “racial" oppression of Blacks of all classes, which played such an important role in the development of the American capitalist system.

Medgar Evers, and others such as Robert Williams, showed the spirit that would later be captured by Malcolm X—freedom “by any means necessary.” Not seeking confrontation or violence, open to pursuing legal channels, but in no way unwilling or unable to defend themselves, they fought to destroy Jim Crow and the scourge of white supremacy.

Fifty years after his assassination, the life of Medgar Evers remains a beacon to all those who seek to dedicate themselves to the cause of liberation from oppression and exploitation. His dedication to the cause continues to inspire us today.

Long live the memory of Medgar Evers!